After a plate of Iberico ham and local cheeses, Don Paco, my host, brings out several bottles of orujo from his cellar for a tasting. This is a fitting end to the meal. It’s a liquid reflection of this forested corner of coastal Spain.

Orujo is a customary after-dinner brandy liqueur made from local grape skins and herbs. It’s made in a variety of flavors, infused with traditional blends of fruits, spices, and sometimes even coffee.

[question_evergreen]

I’m drinking it in Figueiro, a small town in the Rias Baixas region of Galicia, northern Spain. I’m visiting friends who have returned home from living on the Mediterranean island of Ibiza. That’s in Spain too, but its bone-white limestone bays and calm seas are a world away from this wild Atlantic coastline.

Here, we’re closer to Portugal than we are to Madrid. Forget bullfights and olive groves—Galicia is a place of sea mists and secret coves, of high cliffs and rolling grasslands. It’s also home to the pale green grape variety that provides Spain’s most sought-after white wines—Albariño.

Don Paco makes sure I taste from all the bottles, explaining the distillation process that begins after the autumn grape harvests in his vineyards. He explains that the bagasse—the leftover skins and pulp from squeezing the grapes for wine making—is collected and distilled in traditional stills called alambiques. It’s a deceptively simple process that he has been perfecting in his bodega for decades. It produces a brandy he describes, slightly worryingly, as “made in Paco.” I think he means “made in Paco’s bodega.”

I hope he means “made in Paco’s bodega.”

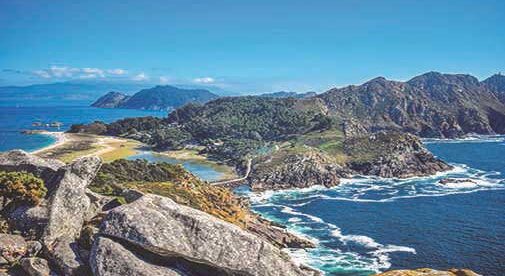

Tucked away in the northwest corner of the Iberian peninsula, Galicia is where Portugal, the North Atlantic, and the Cantabrian Sea meet. The homeland of the ancient Celts, its mountains, forests, and fjords are often overlooked by travelers and expats. They’re unforgettable once you find them, though.

A couple of hundred miles north from the Rias Baixas region, the well-known Camino de Santiago leads to the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. It’s the centerpiece of a medieval town visited by throngs of pilgrims who trek hundreds of miles across the Pyrenees mountains from France in search of spiritual inspiration and dramatic scenery.

However, the Rias Baixas, in the south of Galicia, are mostly known to enophiles (wine lovers). They come to enjoy Albariño—a dry white wine native to these mountains.

This region of deep fjords (rias baixas) marks the frontier of Portugal and Spain. The Miño River separates both countries, flowing west through a wide, fertile valley. It’s the perfect starting point for the Ruta do Viño (Wine Route).

Wine is a way of life here, as it is in most of Spain, but it’s only recently that the vineyards and wineries of Galicia have come to international attention. Right now, it’s in that sweet spot where the tourist infrastructure is there, but the crowds are not.

On the Wine Trail to A Guarda

The Rias Baixas Wine Route covers five subzones of western Galicia. It runs northwards from the border with Portugal, and along the rocky Atlantic coast. Each zone is worth exploring on its own, but O’Rosal in Pontevedra province boasts a wide range of travel and leisure options along with an impressive landscape full of history and nature.

Visitors can explore the O’Rosal subzone, starting their journey at Monte Tecla in A Guarda, the south-westernmost point of Galicia. The panoramic views at the town’s summit, 1,000 feet above sealevel, are breathtaking. The site overlooks Portugal, the Miño, the Atlantic Ocean, and the coastal mountains. What’s more, you can walk through a perfectly preserved Celtic citadel, an archeological site that dates from the 4th century B.C.

After building an appetite, head down to A Guarda’s port for a seafood meal of gigantic proportions. Several restaurants perch on the water’s edge, but at Xeito (Avenida de Fernandez Albor 19) you can enjoy the local seafood while admiring a panoramic view of the town, the port, and the deep ocean. Area Grande restaurant (Playa Area Grande s/n) is a refined option tucked away in a cove near town. There, seafood is also the house specialty, perfect with a bottle of Albariño.

[spain_signup]

Ease your digestion by walking around the pedestrian-friendly coastal town, visit the plazas and craft shops, and admire the ocean views from the observation points. Walk two minutes from the harbor and you can spend the night in the Hotel Convento de San Benito, an exquisite hotel in a 16th-century former convent with a garden, an elegant lounge, and harbor views ($65-95 per night, Praza de San Bieito).

If spending a night steeped in history is not your thing, Vila da Guarda is a straightforward option with modern rooms and apartments in the middle of town ($60-100 per night, Rúa Tomiño, 8).

Inland to Tui

Next morning, follow the Miño upriver and visit the Terras Gaudas winery in O’Rosal to get an idea of where these elegant grapes grow, and why they are so sought after.

Terras Gaudas is one of a consortium of four wineries that represent the four principal wine regions of Galicia. They’re one of the most respected winemaking groups in Spain. All four estates welcome visitors for tasting/educational experiences, although it’s best to book in advance.

After getting your fill and packing a few bottles for the road, head along the river’s banked terraces towards Tui, a walled medieval city on the shores of the Miño originally founded by Romans in the 1st century B.C. The Romans were late to Tui—archaeological findings date habitations in this region to more than 5,000 years ago.

For centuries Tui was, and still is, the official entrance to Galicia for trekkers on the Camino de Santiago. Although the route from France is much better known, and sees more pilgrims, an equally ancient way leads north to Santiago from Portugal.

A walled city originally founded by the Romans.

Walkers mingle on Tui’s ancient cobblestone streets every summer. Start your exploration at the imposing gothic Tui Cathedral that dominates the landscape from the highest point of the city. It’s been the focal point of the town since it was consecrated in 1225 A.D.

Grab a pizza at Restaurante Di Marco, next to the cathedral (Rua Seijas, 4). For a heartier meal, head to a A Muralla Restaurant, a steakhouse with a terrace that overlooks the valley below. It’s a good viewpoint of the impressive town fortifications, too (Rua Sanz, 22, Zona Monumental).

Enjoy the view and your plate of classic Spanish dishes with a glass or bottle of local Caiño or Espadeiro. Both are red wines native to these hills, but known only to the most knowledgeable of wine enthusiasts.

After lunch, walk downhill to stroll along the riverside pathway and enjoy the landscape views of Valenca, another impressive walled city on the Portuguese side of the river.

The Parador de Tui is located farther down the banks of the Miño river ($115 to $200 per night, Avenida Portugal). Paradores are Spain’s state-sponsored hotels and lodgings. Most of them are refurbished historical grand houses and palaces. They’re lavish, high-end, and offer a luxury hotel experience within the surrounds of fairytale properties.

Tui’s parador is an artfully renovated Galician country house built from cut granite and local chestnut beams.

For something a little less formal, the Colón Tuy hotel has large modern rooms and is closer to the center of town ($65 to $120 per night. Colón, 11).

If you are anything like me, after a dose of fortified cities you crave open spaces. Once you’re refreshed and fortified with a good breakfast, head back into the countryside to explore the classy Santiago Ruiz Winery, where you can learn about this family’s traditional winemaking process and their profound influence on the Albariño grape cultivation in the 19th century.

Close out the day at Taperia A Carla in nearby Tomiño, a restaurant tucked into the deciduous forest with well prepared regional food and friendly service.

Nearby, in Figueiro, is where I met Don Paco in his bodega. It’s where I learned about the challenges and rewards of harvesting local grapes, where nothing goes to waste, not even the bagasse.

Traveling through this unspoiled valley between ocean and mountains; from river shores through medieval cities and ancient forests, I learned all about the blend of alchemy and perseverance that turns grapes into wine. And that, with skill, you can also produce orujo—the very essence of this wild corner of Iberia.

[spain_signup]

Related Articles

An Overview of Traditions and Culture in Spain

Five Places to Live in Spain; Two to Avoid

[post_takeover]

[lytics_best_articles_collection]