The process of buying a property in Mexico is the same for all cities, except for the coastal and border areas. These areas, referred to as the zona restringida, are areas in which there are different rules for foreigners (not Mexican nationals). There is nothing wrong with buying in these areas—which are designated as 30 miles from the highest tide and 60 miles from the borders—but the rules are different. In the zona restringida, as a foreigner, you must have a fideicomiso or a bank trust to hold the property. As I understand it, if you have the bank trust, you still own the property—you can sell it, rent it, or build on it. But you must have a trust, which is for 50 years and can be renewed. There is a fee to initiate a bank trust and to maintain the trust. Each bank sets the rate.

Apart from taking into account where your preferred property is located, and if it is part of the zona restringida, you should also consider this advice: Don’t buy a property in an area you have not lived in and, preferably, for at least a year. In other words, like any area anywhere, figure out if you like the town before buying. I believe there is wisdom to this.

Considerations Before Buying

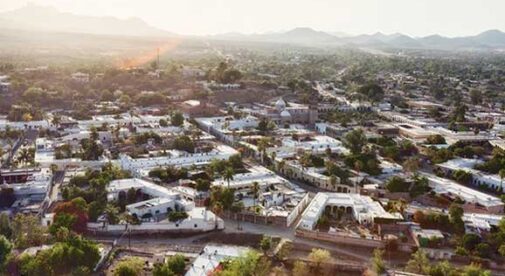

When I first moved to Mexico, I believed I would stay for about three to four months. However, during the second month of living in San Carlos, I realized I did not want to move back to the cold. At that point, I started thinking about whether or not I wanted to buy. For me, the decision was based on the cost of the home, the overall cost of living, the feel of the area, and the technicalities of owning in the town. As San Carlos is in the zona restringida (right on the coast), I realized a bank trust would be needed. I also knew that as a relatively large retirement community for North Americans (Americans and Canadians), it was more expensive to live in San Carlos than in a predominantly Mexican town. As I do not have a large pension, this was meaningful to me—an affordable cost of living is essential. I had put an offer in for local property, and it sold for about $20,000 more than my offer. I put an offer in for another property, and the price was then raised by $10,000. These situations were a little like buying in the United States. So, I started thinking about what my other options were. I wanted to be relatively near the border so I could easily access the U.S. for major medical care (I did not pay into the Medicare system for 40 years for nothing), and I wanted a pleasant climate. I did not care if there was a large North American population. My thinking led me to Alamos.

©AndreaCopp/iStock

I would advise anyone thinking about buying a home anywhere, but certainly out of their home country, to consider what priorities are important to you. Think about the feel of the community, accessibility to services that are important to you, climate, cost of living, and whether the local people must speak your native language. And again, have you lived there long enough to know that you like it? This last criterion is one that many do not heed. Sometimes this works out well. I have a friend who went for a horse ride, found his dream home, and bought it that day. I am not sure he told his wife before he made an offer, but they love the area and have never regretted buying their home. Then there are other people who, on the spur of the moment, make an offer and regret it—or purchase a home only to find out they do not like the town. I am relatively cautious, so I gave it a year before deciding what to do.

[mexico_signup]

Finding a Property in Alamos

When I decided I wanted to buy in Mexico, and that a North American retirement community was not how I wanted to go, I started to look elsewhere. A friend of mine lives in Alamos, a town three hours south of San Carlos, and she encouraged me to look there. She loved the town and had lived there for 15 years full time.

I had visited Alamos twice by the time I decided to consider it seriously. Casually over breakfast, one morning at her place, a friend of hers said to me, “I know of someone selling a house here.” I said, “Let’s go look.” Another friend and I followed the gentleman who knew of the house through the winding colonial streets to an unassuming place about 10 minutes from the center of town. At first glance, I did not like it. There was no kitchen, a huge bed pedestal (made of cement) in the middle of the only room that could be a living room, and bathrooms the size of a small barn. The design to my North American eyes was positively bizarre. I vetoed it immediately, but the man with me, who is Mexican, encouraged me to look at the possibilities. Now, I have always been a sucker for possibilities, so I did look again.

©Mary McCarthy

I returned to San Carlos and thought some more. I asked around locally for a person to inspect the house and found an engineer willing to caravan to Alamos to look at the home. The house was structurally sound, which is primary, although the electric system was scary. He told me that he would charge $3,500 to redo it, but he said, “You can pay less if you do this with a contractor in Alamos.” I knew he was correct. At that point, I began to take this house-buying adventure seriously. The house was about mid-range for a home in that area of Mexico. The price for a North American was a bargain. Even with the $10,000 renovation costs I calculated, and the time needed for the renovation, it was a wise buy. I liked Alamos even with no close beach (which meant fewer hurricanes) and felt comfortable in the town. I knew some Americans and Canadians and several Mexicans in the town, so I was not totally on my own, which I had been when I moved to San Carlos. So I made the offer, but not before I found David Peralta, abogado, my lawyer.

I am not fluent in Spanish or Mexican law. He is. I consulted with him about his work, what he could do, and how much he would charge me. The fee was reasonable. After all, I was paying thousands to buy the home, knowing that all was in order legally was vital to me.

Legal Technicalities

The first thing Mr. Peralta did was find out the conditions in which the seller held the property. He discovered, as did I, that the property was held in a patromonio familiar. Mexican law establishes that a patrimonio familiar is a set of assets, rights, and obligations belonging to a family whose purpose is to protect the family economically and sustain the home. To sell the property legally, the property had to be separated from the patromonio familiar. This legal vehicle is somewhat similar to some properties in the United States. Trusts are often established to hold property in the family’s control across generations. No actual closing could occur without this being fixed. The resolution took two months or so and, finally, we were ready to close.

©Mary McCarthy

In Mexico, the finalization of any deed and property is done with a notario publico, trained as a lawyer and appointed by the governor of the state. Then, they search the title, which is a somewhat complicated process as much of Mexico was Spanish Land Grant property, and you need to know the chain of title is legal. The process can take a while. In my case, this process took another six weeks or so. Then Mr. Peralta and I were ready. We traveled to Alamos and met the owner, who I had talked with before this meeting (facilitated by Mr. Peralta). The owner, her husband, the notario, Mr. Peralta, and I were present. Even in Spanish, and with a bit of my nervousness, it was not an arduous process to complete. The seller’s husband knew a little English, was friendly, and, I think, was trying to relax me. My lawyer was certainly trying to calm me down. There is nothing like handing over thousands of dollars to near-perfect strangers to make one a bit nervous.

There was, of course, a problem with my U.S. bank (isn’t there always?). Even though I had given them a heads up about my purchase, their demands for transferring the money bank to bank were challenging. I wound up simply writing a check. Then the final wait began.

Final Steps

As a foreigner, the property had to be registered both in the town and then in the state. A foreigner acquiring property outside the restricted area must obtain a permit with the Secretary of Foreign Affairs. So commenced another wait, which I am still in the middle of. It is quite a process, but not surprising. The difference is once the property is registered; it is mine. The bank does not own it. Another difference is the yearly taxes, which are considerably less than in the average town in the U.S. Finally, there is no fideicomiso and no yearly bank payment. A low tax bill is all I will pay. For me, this is a good idea. Living in a home I own, with a low cost of living, still near a beach (about an hour and a half away), in a comfortable and quiet town, I suspect I will settle in happily. I will update you once the process is finished.

[mexico_signup]

Related Articles

Mexico Real Estate & Property Listings

Real Estate & Property Information for San Miguel de Allende

Real Estate & Property Information for the Riviera Maya

[post_takeover]

[lytics_best_articles_collection]