We bought the kitchen table for our new home in Mexico’s Yucatán from a guy on a bike. He’d heard through the grapevine we were building a house and with the usual tenacious work ethic of the local Maya, he pedaled from the town of Valladolid (15 miles away) to make a sale… table and stools balanced and tied to his bike.

Building (and furnishing) a house is not for the faint-hearted… especially when you decide to build it in the Mexican jungle. But that’s exactly what my wife Diane and I did in the tiny Maya village of Ek’Balam, total population: 492.

I first visited Ek’Balam (“black jaguar”) on a writing assignment. It’s the site of ancient Maya ruins… just like those in Indiana Jones, with temples dating back millennia, stone beds, and menacing guard posts where soldiers once patrolled.

Though sleepy now, between 700 and 800 AD, Ek’Balam was a major city and home to some 20,000 Maya. It was largely abandoned in the 11th century… lost to the jungle until it was excavated in the 1990s.

Now, tourists can admire the famous “angels” depicted on the walls of the main ceremonial site as well as the names of rulers dating back to 770 AD. Ancient texts are still kept in these rooms. Although only a fraction of the 10-mile ceremonial site is tourist-friendly, it’s well worth the visit and the entry fee of $26.

But the real appeal of this part of the Yucatán is the quiet, tight-knit community—locals are welcoming and friendly to foreigners. So in 2016, when Diane and I decided we needed a break from our fast-paced life in Cancun, we chose to live in Ek’Balam.

While rural by any definition, Ek’Balam is hardly off the grid. We’re about a 30-minute drive from the town of Valladolid (population 60,000), where we can grocery shop as needed. Our electricity bill arrives every other month. Water is free (provided by the village), and while the roads need some work, they’re navigable by our Jeep. We can stream Netflix and Skype our friends… most days. And it’s where we’ve now built our full-time retirement home. See a full set of photos below:

A Home That Combines the Best of Two Worlds

We wanted a modern, one-floor, air-conditioned building with good plumbing and electric infrastructure. But while attractive, traditional Maya homes are humble by Western standards.

Called nahs, they’re an amalgamation of their local natural surroundings. Foundations are made from field stones. Walls are constructed from local saplings. Roofs are thatched with interwoven palm leaves and tied together with strips of bark. They’re lightweight and rainproof. The vertical sapling walls are the jungle’s answer to air con.

The only other materials used in these nahs are cement for the foundation and whatever plumbing and electrical supplies the owners decide upon.

While we knew we wanted to embrace local living, a nah wasn’t for us. But the typical wood frame structures common in the U.S. are not a thing here. Bugs eat most types of wood and we’re in the jungle… it’s an endless buffet for the termites and carpenter ants. Plus, the Yucatán peninsula is nestled between the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico. Tropical storms and hurricanes sometimes pass through, destroying the wooden structures.

So to pull off our dream home, we knew we’d have to build a durable concrete block and natural stone structure, with steel-reinforced columns and beams. This home would not sag, settle, blow down, flood, or burn… it would be a veritable fortress with features that would allow us to age in place.

Most properties here have small vegetable gardens and fruit-bearing trees. Many also have small farms (fincas) in the area, where the primary crops are squash and corn that is hand-ground into flour for tortillas. Families are heavily reliant upon the food they grow, and it’s not uncommon to see uniformed students pluck fruit from the trees while walking to school.

While we have no garden, we do keep a supply of candy on hand for the village children who stop by for impromptu English lessons from Diane, a retired teacher.

Materials Sourced a Stone’s Throw Away

A stonemason individually selected each stone used on the ornamental front facia of our home. Several pedal carts were used to laboriously transport them from where they were handpicked just outside the village. The stonemason and his helper sized and cemented each stone into place to create a decorative, abstract mosaic, fitting each stone into place like pieces of a puzzle.

We watched them use simple tubes of water in place of levels to ensure correct wall alignment, just as their ancestors did.

Stone- and block masonry is a trade passed from father to son and has been a part of the Maya culture for thousands of years. The nearby ruins of ancient pyramids prove that!

The Grand Entrance

We discovered our main entry door in the dusty corner of a small local shop in nearby Valladolid. Even buried beneath multiple coats of thick black paint, we saw its potential.

The door weighs about 85 pounds. It’s robust and dense with gorgeous Spanish hand carvings. A visiting anthropologist dated the door to the 1600s, when the invading Spaniards had first enslaved the Maya people.

Five weeks of labor and love from a skilled local cabinet maker in Valladolid revealed the stunning color and grain of the Spanish cedar beneath all that paint… and you can see the tool marks left by the original craftsman nearly 500 years ago.

We’ve never locked this door in the seven years we’ve been here. Small village living is safe; there’s virtually no crime. Instead of serving as a barrier, our door is what welcomes us—and our guests—home.

Open Doors and Open Hearts

We went on the hunt for more beautiful historic doors, joking that we were rescuing old doors like some folks rescue cats. We wanted these tangible pieces of Maya history to be integral parts of our home.

From an antique dealer in Mérida we retrieved a pair of beauties from the 1700s. They open in the center, and likely once served as the entrance to a Spanish colonial home or business.

But the doors needed to be cut down, strengthened, and refinished before we could hang them. A local skilled craftsman-turned-friend spent weeks on sanding and repairs… and now those doors hang proudly in our side entrance.

That skilled craftsman lives next door and he and his family are regular visitors to our home. Though we always compliment his work, the local culture is one of humility. Pride is frowned upon; it’s assumed that all work is done well. Our door serves as not only a reminder of the history of our new abode, but of the unique community we’ve joined here.

A Window Into the Yucatán’s Artisanal Past

In Mérida, about a three-hour drive northwest, we commissioned window coverings from a family of women known for their handwoven reeds

These craftswomen take their wares being “locally sourced” literally. When we we made our request, they told us it’d be a couple weeks before the reeds were tall enough to harvest for our project. Because the craftswomen gather them from the saltwater marshes, the reeds are only seasonally available. The length of the reeds dictates the purposes for which they may be used, whether it be as wall decor, placemats, or closet coverings.

We’ve never locked our front door in 7 years.

Weaving is popular across rural Mexico. In our village, women quietly weave hammocks on crude wooden looms. Complex patterns are memorized and passed down through generations, and date back to ancient times.

These hammocks are often sold to brokers who distribute them to tourist shops across Mexico and the U.S. and to the occasional tourist who finds their way into our village.

Aging in Place With Locally Made Materials

The bathroom is a work in progress, but we designed it as a totally open space, including the shower area. The entire floor is covered in non-skid tile, with glossy tile covering the shower walls. (In fact, all floors throughout the house are covered in non-skid tile, which is safe and easy to clean… ideal as we age.)

Best of all, these ceramic-coated clay tiles come from nearby—the Coahula region of northwest Mexico.

Joining the Table

The kitchen serves as a central work area, with standard countertops and wooden cupboards hung around the walls. It has a modern refrigerator/freezer, gas range/oven, and microwave, all procured from Home Depot and Costco in Mérida. Nearby Valladolid sells appliances, too.

The kitchen table (the one delivered by bike) is made from local cedar. The wooden butcher-block table and two stools were handcrafted by one of the hundreds of local men who have such skills.

A $36,000 Labor of Love

To date, we’ve spent $36,000 on the house. We still have some work to do, but there’s no rush. Our home is a work in progress as we constantly bring in new-to-us furniture and decor that reminds us of the reason we moved here: the community. We’ll always have a fresh project… and more local craftsmen to meet.

A TRADITIONAL MAYA WEDDING CEREMONY

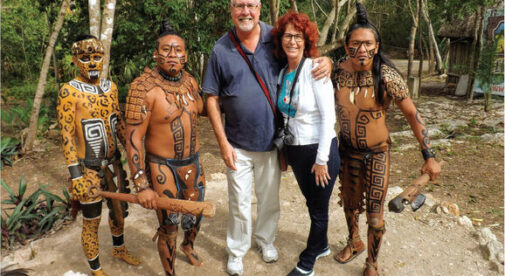

For our 20th anniversary, Diane suggested that we celebrate in a way befitting our adventurous marriage. So we had a traditional Maya ceremony here in the village.

These ceremonies are held to celebrate weddings, birthdays, communal holidays, or the recognition of an ancient event. We distributed invitations to most of the village and arranged for the warriors to perform a traditional wedding ceremony. By then, the warriors and village residents were no longer just our neighbors, but our friends… and they were eager to pitch in.

A clearing was prepared in the nearby jungle. Rocks were used to line a pathway to the ceremonial altar. Wildflowers decorated the ground. The 50-minute ceremony was translated from Maya to Spanish by one of the warriors. Afterward, they danced and chanted while incense burned nearby. We were celebrating our love for not only each other, but for our new home.

And we brought our own culture to the table, too… providing cake and American beverages when the ceremony concluded.

[mexico_signup]

Related Articles

Guide to San Miguel de Allende, Mexico

How to Move to Mexico – Complete Guide

An Overview of Traditions and Culture in Mexico

[post_takeover]

[lytics_best_articles_collection]